Best States and Tax Benefits for Startups: A Comprehensive Guide

For startups, your for-profit, state-law entity choices are (1) LLC or (2) corporation. If you’re a Startup, we’re assuming you have plans to (either...

5 min read

Chris Daming, J.D., LL.M.

:

Aug. 6, 2024

Chris Daming, J.D., LL.M.

:

Aug. 6, 2024

When deciding between an LLC or S Corp, it’s important to fully understand the implications of each option for both state law and tax law. This is because you could be an LLC or Corporation (both are state law entities) taxed as an S Corporation (a tax law entity). Or you could form an LLC and be taxed under the default rules (i.e. disregarded entity or partnership, depending on how many members you have). Confusing, right? Don’t worry—we cover everything about choosing the best business entity in our comprehensive guide.

Legal GPS Pro

Protect your business with our complete legal subscription service, designed by top startup attorneys.

To help you navigate this decision, we’ll break this blog down into two steps:

One last thing - here's a handy chart to reference if you get confused. If a business has one owner, you have five choices:

For single-owner businesses, you generally have two choices for your state law entity: LLC or Corporation. More often than not, LLCs are the preferred choice for most small businesses. Here’s why:

Simplicity: LLCs are easier to form than corporations and often preferred, as highlighted in our Sole Proprietorship vs. LLC comparison. They also require fewer ongoing formalities. Corporations are required to hold annual shareholder meetings, elect a board of directors, and maintain detailed corporate records, which can be burdensome for a single-owner business.

Flexibility: LLCs provide more flexibility in how you manage and operate the business. With corporations, more formalities, like annual meetings and elections, are required, making them more complex and time-consuming.

While LLCs often provide a more straightforward approach, it’s worth noting that some attorneys may recommend a corporation simply because they are more familiar with it. However, unless you have specific reasons for choosing a corporation, an LLC will typically offer a simpler setup and ongoing maintenance process for small businesses.

Corporations—especially S Corporations—come with more administrative work. For example, an S Corp must file:

While some of this administrative burden can be outsourced to a payroll service (for around $50/month), it still adds a layer of complexity.

LLCs generally offer the same or better liability protection than corporations. Two key points to consider:

Corporate Veil: LLCs make it easier to maintain the “corporate veil,” which protects your personal assets from business liabilities. Corporations are required to maintain strict corporate formalities, and failing to do so can lead to “piercing the corporate veil,” which could result in personal liability. LLCs have fewer formal requirements, making it easier to preserve this protection.

Charging Order Protection: This is like a reverse corporate veil. It protects the business from the personal liabilities of its owners. If an LLC owner has a creditor, that creditor can only place a lien on the owner’s distributions from the LLC, but can’t seize the LLC’s assets or take over the business itself.

In some states, LLCs have higher fees than corporations, such as in California, where LLC fees are significantly more expensive. If you’re operating a small or hobby business, these fees might make a corporation more appealing. Always check your state’s fee structure before deciding.

Legal GPS Pro

Protect your business with our complete legal subscription service, designed by top startup attorneys.

Once you’ve selected your state law entity (likely an LLC), the next step is to choose your tax law entity. For most small businesses, the two most common choices are:

If you’ve chosen a corporation as your state law entity, you will almost always select S Corp for tax purposes unless you’re a larger startup with different needs. But since most small businesses are LLCs, let’s focus on whether you should elect to be taxed as a disregarded entity or as an S Corp.

Most small businesses start as LLCs taxed as disregarded entities. As the business grows and becomes more profitable, they then elect to be taxed as an S Corp to take advantage of certain tax benefits. Here’s why:

To determine whether it makes sense to elect S Corp status, you need to know what the IRS would consider a reasonable salary for yourself. The IRS has guidelines, but in general, it’s the amount you would be paid if you were doing similar work for another company.

You can use resources like salary.com, glassdoor.com, or your local public library to get an idea of what a fair salary would be for your role.

Disregarded Entity: If you’re just starting out or not yet profitable, being taxed as a disregarded entity (the default for single-member LLCs) is simpler. You report your business’s income on your personal tax return and avoid the complexity of payroll and corporate tax returns.

S Corporation: Once you’re profitable, electing S Corp tax status can provide significant tax savings. This is especially true when your business is generating enough income to pay yourself a reasonable salary and still have profits left over.

LLCs taxed as disregarded entities pay self-employment taxes on all net earnings (15.3%, which covers Social Security and Medicare). However, with an S Corp, you only pay these taxes on your salary—not on any additional profits. This can lead to substantial tax savings as your business grows.

For example, if your business earns $75,000 or more, many CPAs recommend considering an S Corp election to reduce the self-employment tax burden.

You don’t have to make the decision to elect S Corp status right away. Many businesses start as disregarded entities, then once they become profitable, they elect S Corp status. To initiate the S Corp election process, you’ll need to file Form 2553 with the IRS. You'll also want to update your operating agreement.

For many small businesses, the best approach is to start as an LLC taxed as a disregarded entity and transition to an S Corp once the business becomes profitable. This approach allows you to keep things simple in the early stages, while still taking advantage of tax savings when your business starts making money.

If you need more guidance on choosing the right state or tax law entity, check out our comprehensive LLC vs. S Corp vs. C Corp guide.

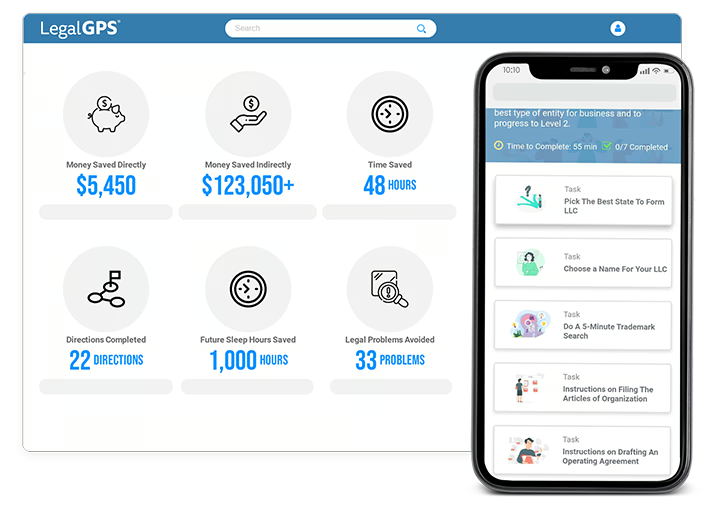

The biggest question now is, "Do you need a lawyer to start a business?” For most businesses and in most cases, you don't need a lawyer to start your business. Instead, many business owners rely on Legal GPS Pro to help with legal issues.

Legal GPS Pro is your All-In-One Legal Toolkit for Businesses. Developed by top startup attorneys, Pro gives you access to 100+ expertly crafted templates including operating agreements, NDAs, and service agreements, and an interactive platform. All designed to protect your company and set it up for lasting success.

Legal GPS Pro

Protect your business with our complete legal subscription service, designed by top startup attorneys.

For startups, your for-profit, state-law entity choices are (1) LLC or (2) corporation. If you’re a Startup, we’re assuming you have plans to (either...

Are you an LLC owner thinking about electing to be taxed as an S Corp? If you're still not exactly sure what is an S Corp v. C Corp, or are unaware...

1 min read

When figuring out your “choice of entity,” you first want to make sure it even makes sense for you to form an LLC. Sometimes, remaining as a sole...